I rode my bike over to the Hispanic Cultural Center on Saturday. Albuquerque has been celebrating Cesar Chavez Day for about twenty-six years. This year's event was well attended, honoring the farm worker organizer and also the rise of many women to positions of leadership at all levels of government.

I tried shots of the Chavez poster from several angles, deciding finally on this image reflected in the windows of the Cultural Center. The day's speeches were interspersed with dancers and singers.

No event in Old Town or Barelas is complete without this fellow officiating en dos idiomas.

Of course, at least one mariachi group is also mandatory.

The star performer was this little girl who danced for her mother and Cesar Chavez.

Our new mayor, Tim Keller, made a brief appearance at the beginning of the celebration, but the ladies owned the stage. Michelle Lujan Grisham, the newly elected Governor of New Mexico, is always the shortest person in any assembly of politicians, but she has a personality at least seven feet tall. The woman under the fedora to the right is Dolores Huerta, native New Mexican, co-founder of the United Farm Workers and keynote speaker for the Cesar Chavez Day celebration.

Next to the Governor in this shot is Deb Haaland, one of two Native American women who made it into the U.S. House of Representatives this year.

Quite a day for New Mexico.

I shot two rolls of Tri-X at the celebration, but brought home fewer pictures than I had hoped for due to some apparent malfunction of the Minolta X-700. Most of the photos were under-exposed and some in full sun were grossly so. Not sure if the problem is electrical, mechanical or the the result of creeping senility -- possibly a combination of all three. The manual says that in aperture-priority mode the camera should work properly with about any Minolta lens, but I'm wondering if using the old MC 135 lens may be a source of problems. I'll work with the issues as I really like the camera and the set of lenses I have for it.

My plan was to develop one roll in the usual HC110b and the other using semi-stand development. When I saw the results of the first roll, however, I decided to forego the stand dev as the complications left no room for meaningful comparison. I still feel I'm making some progress at sorting out variables in the results of my photo efforts, but it is slow going.

----------

Update:

I shot a test roll with the camera to systematically compare results from the three lenses I have for the Minolta X-700. The camera works fine in all three shooting modes with the normal and wide-angle lenses. The shots from the 135mm lens degraded in quality as I moved through the roll. On closer examination I see that the aperture stop-down mechanism is sluggish, probably due to dirt on the aperture blades and other moving parts. I'm not sure I have the energy available to tackle the dismantling of the lens a second time. I have gotten some satisfaction from figuring out the problem and verifying that the camera and two of the lenses are working properly.

Monday, April 01, 2019

Saturday, March 30, 2019

Recalibrating

I've had some inconsistent results from my home film processing lately, so I decided to try to iron out some of the variables in the process. I got a new bottle of HC110 developer and a new digital thermometer from Freestyle along with a batch of TMAX and Tri-X film. I am thinking I will also do more stand and semi-stand developing as that makes time and temperature less important as well as providing some improvement in b&w tonal qualities. The last couple rolls I shot were processed normally in HC110 dilution B, so I'll try the next couple using semi-stand for comparison.

Today is Cesar Chavez Day in Albuquerque, so I'm hoping to get to the celebration at the Hispanic Cultural Center with the Minolta X-700 and some Tri-X. Lots of new photo opportunities on the horizon with the arrival of Spring.

We have had some good ballooning weather lately. This Stars and Stripes model came slowly down our street last Sunday at just over roof level. I grabbed the Leica and walked along with the balloon thinking I might get some shots of a landing as that was pretty clearly what the pilot was aiming for. However, there were really no likely landing spots on the course chosen by the wind, so about six blocks on the pilot gained some altitude and speed and left me behind.

A few days later I took my Retina Reflex loaded with another roll of TMAX 100 to the botanic garden. I was the first one through the gate at 9:00 AM and it was nice to have the place to myself except for a few groundskeepers doing their watering and weeding.

Today is Cesar Chavez Day in Albuquerque, so I'm hoping to get to the celebration at the Hispanic Cultural Center with the Minolta X-700 and some Tri-X. Lots of new photo opportunities on the horizon with the arrival of Spring.

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

Newhall's History

I like reading about the history of photography, but I've been haphazard in pursuing the subject. I was pleased recently to locate a copy of Beaumont Newhall's The History of Photography at a library book sale for just a couple bucks. This last edition looked nearly twice the size of earlier ones.

Newhall was a pivotal figure in drawing attention to the "straight photography" style as practiced by such notables as Adams and Weston. His "History" first appeared as a companion publication to an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939. Besides a stint as a curator of photography at the MOMA, he also got the photography gallery under way at the George Eastman House in Rochester. Newhall spent years as a teacher at the University of New Mexico and developed the school's photography program.

As an art historian Newhall developed an early interest in photography and brought a scholarly focus to the subject. His recounting of photography's heroic 19th Century phase gives a clear view of the technical developments of the period along with the amazing stories of the major actors who took their giant wet plate cameras into the wilderness along with their darkrooms on wheels pulled by mule teams. As a curator, Newhall championed the work of Stieglitz, Strand, Weston and many others whose stylistic innovations dominated fine art photography into the mid-Twentieth Century.

Newhall endeavored to keep his history up to date with four editions after the first, but in reading the later parts of the book questions seem to pile up faster than answers. An overview is provided of major trends such as the development of documentary and photojournalistic work and some of the major players are mentioned, but there is not the same focus on style and substance which Newhall brought to examining the luminaries of the 1930s and '40s. Newhall lists the well known names of early Life magazine photographers and ticks off the war reporters such as Capa and Duncan. He pays attention to those who struck out in new directions such as Cartier Bresson, Winogrand and Arbus. However, in the final edition there is, inexplicably, no mention of the whole Civil Rights era and its chroniclers. Where, for instance, is Gordon Parks and his history with the FSA and Life? Where is Roy Decarava who was a fine arts star promoted by Szarkowski with solo exhibits at the MOMA? Based solely on Newhall's account, one would have to assume that there were no black Americans who owned cameras. By 1982 when the last edition of Newhall's "History" appears such omissions are unforgivable.

I think there are at least a couple important factors which contributed to the inadequacies of Newhall's final "History". Firstly, the book is not really a history of photography. It is a history of the elitist fine arts establishment; there was a lot more to photography than that by 1982. The other likely source of problems is that the book was promoted by the publisher as a text book and it was likely used widely in university photography programs. Such texts are typically updated annually with additions of dubious value to ensure that students buy new books rather than relying on the second hand market to meet class requirements. I do not know to what extent teachers in higher education relied on Newhall's book as a basic source for instruction, but I would hope that they drew on other sources to supplement the view offered by Newhall's text.

Newhall was a pivotal figure in drawing attention to the "straight photography" style as practiced by such notables as Adams and Weston. His "History" first appeared as a companion publication to an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939. Besides a stint as a curator of photography at the MOMA, he also got the photography gallery under way at the George Eastman House in Rochester. Newhall spent years as a teacher at the University of New Mexico and developed the school's photography program.

As an art historian Newhall developed an early interest in photography and brought a scholarly focus to the subject. His recounting of photography's heroic 19th Century phase gives a clear view of the technical developments of the period along with the amazing stories of the major actors who took their giant wet plate cameras into the wilderness along with their darkrooms on wheels pulled by mule teams. As a curator, Newhall championed the work of Stieglitz, Strand, Weston and many others whose stylistic innovations dominated fine art photography into the mid-Twentieth Century.

Newhall endeavored to keep his history up to date with four editions after the first, but in reading the later parts of the book questions seem to pile up faster than answers. An overview is provided of major trends such as the development of documentary and photojournalistic work and some of the major players are mentioned, but there is not the same focus on style and substance which Newhall brought to examining the luminaries of the 1930s and '40s. Newhall lists the well known names of early Life magazine photographers and ticks off the war reporters such as Capa and Duncan. He pays attention to those who struck out in new directions such as Cartier Bresson, Winogrand and Arbus. However, in the final edition there is, inexplicably, no mention of the whole Civil Rights era and its chroniclers. Where, for instance, is Gordon Parks and his history with the FSA and Life? Where is Roy Decarava who was a fine arts star promoted by Szarkowski with solo exhibits at the MOMA? Based solely on Newhall's account, one would have to assume that there were no black Americans who owned cameras. By 1982 when the last edition of Newhall's "History" appears such omissions are unforgivable.

I think there are at least a couple important factors which contributed to the inadequacies of Newhall's final "History". Firstly, the book is not really a history of photography. It is a history of the elitist fine arts establishment; there was a lot more to photography than that by 1982. The other likely source of problems is that the book was promoted by the publisher as a text book and it was likely used widely in university photography programs. Such texts are typically updated annually with additions of dubious value to ensure that students buy new books rather than relying on the second hand market to meet class requirements. I do not know to what extent teachers in higher education relied on Newhall's book as a basic source for instruction, but I would hope that they drew on other sources to supplement the view offered by Newhall's text.

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

This is not a test

At least it is not a test of the camera or the lens. The Leica IIIa is ... well, a Leica. The Jupiter-8 is a superlative 6-element Sonnar design which the Russians appropriated along with the whole Zeiss establishment as reparations after WWII.

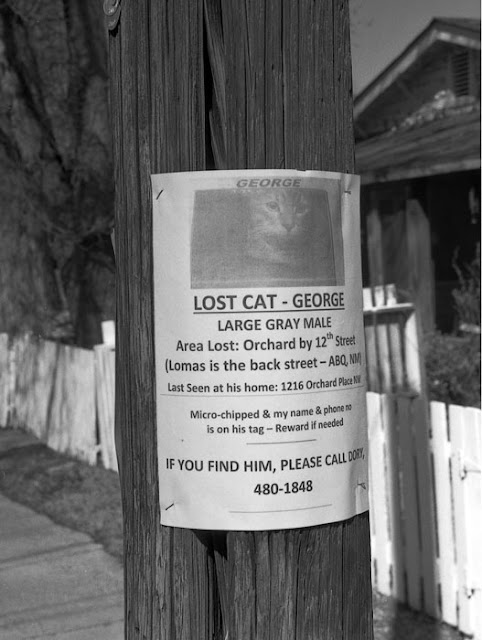

The question to be addressed is that of compatibility. There is a lot of angst expressed in on line forums about slight differences in the lens mount to focal plane distances between Leicas and their Soviet counterparts. People report making precise measurements with their micrometers and even shimming their Soviet lenses to compensate for the perceived problem. So, when I confront a matchup of my Leica with a new Soviet lens, I make sure I shoot at a variety of distances to assure myself that both the lens and the camera are performing up to the expected standards. The following shots are from a roll of TMAX shot on a recent neighborhood walkabout.

I'm not seeing a problem. In fact, I've shot several Russian lenses with the Leica including FED, Jupiter and Industar models in 50mm and 35mm focal lengths without any loss of sharpness that is apparent to my eyes. There may be a real problem lurking out there and maybe I'll encounter it one day, but I'm not likely to lose any sleep over the possibility. I also have failed to find any apparent difference from the results I get when the Soviet lenses are mounted on the Soviet cameras they were built for.

I've had a Jupiter-8 lens for my Contax-copy Kiev IIa for a long time. That lens is about ten years older than my recently-acquired Leica-Thread-Mount Jupiter, but it is also an excellent performer. I haven't used it much, partly because I usually prefer to get out with the the Jupiter-12 35mm lens on the Kiev. However, The Kiev also does not offer the same level of compact precision as the Barnack Leica.

Besides adding a nice tactile dimension to the shooting experience, the Leica's slick operation instills confidence while also providing some practical enhancement to my shooting results. For instance, that buttery-smooth film advance mechanism yields a strip of exposures that are very narrowly separated and perfectly spaced, with the result that I can often get 25 frames from a 24-shot roll even with the long tapered leader the Leica requires.

The bottom line for me on the issue of the compatibility of the Leica and Soviet lenses is that the combination provides a practical and economical way to the Leica experience. If the Leica were my only camera, I would be more concerned with the likelihood that there could be a problem with lenses with a focal length greater than 50mm. Obviously, I have a lot of other choices of cameras if I feel the need to use long lenses.

The question to be addressed is that of compatibility. There is a lot of angst expressed in on line forums about slight differences in the lens mount to focal plane distances between Leicas and their Soviet counterparts. People report making precise measurements with their micrometers and even shimming their Soviet lenses to compensate for the perceived problem. So, when I confront a matchup of my Leica with a new Soviet lens, I make sure I shoot at a variety of distances to assure myself that both the lens and the camera are performing up to the expected standards. The following shots are from a roll of TMAX shot on a recent neighborhood walkabout.

I'm not seeing a problem. In fact, I've shot several Russian lenses with the Leica including FED, Jupiter and Industar models in 50mm and 35mm focal lengths without any loss of sharpness that is apparent to my eyes. There may be a real problem lurking out there and maybe I'll encounter it one day, but I'm not likely to lose any sleep over the possibility. I also have failed to find any apparent difference from the results I get when the Soviet lenses are mounted on the Soviet cameras they were built for.

I've had a Jupiter-8 lens for my Contax-copy Kiev IIa for a long time. That lens is about ten years older than my recently-acquired Leica-Thread-Mount Jupiter, but it is also an excellent performer. I haven't used it much, partly because I usually prefer to get out with the the Jupiter-12 35mm lens on the Kiev. However, The Kiev also does not offer the same level of compact precision as the Barnack Leica.

Besides adding a nice tactile dimension to the shooting experience, the Leica's slick operation instills confidence while also providing some practical enhancement to my shooting results. For instance, that buttery-smooth film advance mechanism yields a strip of exposures that are very narrowly separated and perfectly spaced, with the result that I can often get 25 frames from a 24-shot roll even with the long tapered leader the Leica requires.

The bottom line for me on the issue of the compatibility of the Leica and Soviet lenses is that the combination provides a practical and economical way to the Leica experience. If the Leica were my only camera, I would be more concerned with the likelihood that there could be a problem with lenses with a focal length greater than 50mm. Obviously, I have a lot of other choices of cameras if I feel the need to use long lenses.

Labels:

HC-110B,

Jupiter-8,

Kodak Tmax 100,

Leica IIIa,

semi-stand development

Saturday, March 09, 2019

Walking the River Trail

Albuquerque's weather has taken a turn for the better and I was able to get in a couple walks this week in the riverside forest. My first walk went from the Rio Bravo bridge to about half a mile north. Fisherman take trout from the irrigation channel near the bridge, but there are not many walkers and bikers in the area and I saw no one else on the trail. I'm thinking I'll try walking the whole three-mile stretch between Rio Bravo and Cesar Chavez sometime soon. That is about my limit these days, so I'll probably drop off my bike first at the Hispanic Cultural Center to give me a way to get back to my truck.

There is a long unbroken barrier of flood control jetty jacks along this section of the river. Many of the jetty jacks are far from the river's course now and serve no useful purpose other than as a reminder of the complicated history of water management along the Middle Rio Grande.

I carried along my Minolta X-700 on both walks and shot with all three lenses I have for the camera. They all performed well, though I still need to get some lens shades, particularly for the 28mm.

There is a long unbroken barrier of flood control jetty jacks along this section of the river. Many of the jetty jacks are far from the river's course now and serve no useful purpose other than as a reminder of the complicated history of water management along the Middle Rio Grande.

I carried along my Minolta X-700 on both walks and shot with all three lenses I have for the camera. They all performed well, though I still need to get some lens shades, particularly for the 28mm.

Labels:

Bosque,

Kentmere 100,

Minolta X-700,

PMK Pyro,

Rio Grande

Monday, March 04, 2019

Goodbye to Old Friends

Not these two. They're in good shape and sticking around.

I'm not sure how long that bottle of Rodinal has been sitting in my refrigerator. It could be six or eight years. Acros and Rodinal has long been a favorite of mine for medium format work, but it looks like the end of the line for this combination. Fuji has stopped making Acros. I still have a few rolls left, but anything left out there is going to be prohibitively priced from here on in, and I'm going to move on. I could get a replacement bottle of Rodinal easily enough, but I think I'm better off using a couple other developers that I like including PMK Pyro and HC-110, both of which also have good shelf life.

The reason the two portrait negatives were closer to appropriate density is that I braced the camera on a tripod and shot with a cable release with a best-guess exposure in the neighborhood of a quarter second. So, the modified BHF got the job done well enough.

Once I've used up my last rolls of Acros I'll likely shoot TMAX 100 in my simple cameras most often. There are plenty of other choices still available, though, so still some room for experimentation.

I find myself also dealing with some other changes in the way I handle film. I recently refurbished an IMAC by cleaning it up and adding some memory. The computer has a very nice 21-inch display and it seems about as fast and responsive as my laptops running Windows 7, Window 10 and Linux Mint. I'm using the IMAC now for most of my on line activity, so that means I only have to turn on my old Windows XP desktop to scan negatives using PhotoShop and SilverFast. Down the line I'll probably have to look for a scanner and some software compatible with the IMAC. I'm currently taking a stab at learning to use the free GIMP photo editing program, but it has what seems like a nearly impenetrable user interface. Such is life, I guess.

Those were the only shots I liked out of a roll of 12 shots from my Brownie Hawkeye Flash box camera. The rest were shot outdoors in mostly sunny conditions, but they looked underexposed by one to three stops. That is an unlikely outcome with any box camera loaded with 100-speed film as such conditions should actually result in slight overexposure.

Here is the problem:

The reason the two portrait negatives were closer to appropriate density is that I braced the camera on a tripod and shot with a cable release with a best-guess exposure in the neighborhood of a quarter second. So, the modified BHF got the job done well enough.

Once I've used up my last rolls of Acros I'll likely shoot TMAX 100 in my simple cameras most often. There are plenty of other choices still available, though, so still some room for experimentation.

I find myself also dealing with some other changes in the way I handle film. I recently refurbished an IMAC by cleaning it up and adding some memory. The computer has a very nice 21-inch display and it seems about as fast and responsive as my laptops running Windows 7, Window 10 and Linux Mint. I'm using the IMAC now for most of my on line activity, so that means I only have to turn on my old Windows XP desktop to scan negatives using PhotoShop and SilverFast. Down the line I'll probably have to look for a scanner and some software compatible with the IMAC. I'm currently taking a stab at learning to use the free GIMP photo editing program, but it has what seems like a nearly impenetrable user interface. Such is life, I guess.

Saturday, February 23, 2019

Winter Light

Central New Mexico weather gets complicated in February. Sunny, warm days create an impression of Spring being just around the corner. Winter then reasserts itself with numbing cold, gray skies and snow flurries. Carrying my little Olympus Infinity Stylus in my pocket helps me cope with the unpredictability.

Saturday, February 16, 2019

HIgh Tech

Margaret has a small collection of orchids on a table in the southeast corner of our living room. I think all have been given to her by friends who have given up on the plants after their initial blooming. Margaret's success in reviving the plants seems to be based mostly on providing a brightly lit location, once-weekly watering and a large dose of patience.

When I was a kid in the 1950s orchids were rare and expensive. Hobbyists grew orchids in elaborate temperature and humidity-controlled hot houses. The main commercial outlets were florists which made the cut flowers available mostly in the form of corsages for teenage mating rituals.

Today, an astounding variety of blooming orchids can be found in about any supermarket, priced low enough to encourage impulse purchases. The horticultural innovations along with production and marketing techniques rival those of the computer industry in their complexity. The best description I found of the current state of the industry through a quick Google search was an article hosted at Perdue, Development of Phalaenopsis Orchids for the Mass-Market by R.J. Griesbach. The final two paragraphs nicely sum up the amazing industrialization of orchid production and where it is headed:

Phalaenopsis production is now international in scope. For example, in one operation breeding occurs in the United States. Selected clones are sent to Japan where tissue culture progation is initiated. Successful cultures are then sent to China for mass proliferation. In vitro grown plantlets are next sent to the Netherlands for greenhouse production. Finally, flowering plants are returned to the United States for sales. Very few Phalaenopsis are bred, propagated, flowered, and sold in the same country.

At this time, production does not meet the demand. It is widely expected that sales will increase as production increases. Demand for Phalaenopsis should continue well into the future as new types are developed. Based upon today’s breeding efforts, the cultivars of the future will have a compact growth habit, variegated foliage, fragrance, and be ever flowering.

Labels:

Kodak Color Plus 200,

Minolta X-700,

orchids,

Unicolor C-41

Wednesday, February 13, 2019

On Slowing Down

I've found myself lately making some stupid mistakes in my photographic endeavors. It seems pretty clear to me on thinking it over a bit that I'm not now - maybe never have been - particularly good at multi-tasking. I seem to have quite a variety of interests and obligations and it is clearly a mistake to try to take care of more than one or two at a time. So, I'm going to try to slow things down a bit and try to focus better on each thing , and keep my priorities straight.

Part of my problem involves the generosity of friends. Recently, I have been gifted several fine cameras and an Apple IMAC. I'm thrilled to have each of those items, but I've got to do a better job of pacing myself in taking advantage of my sudden wealth of opportunity. The IMAC, for instance, is particularly welcome as a chance to learn to use an Apple system. People occasionally ask me for help with their computers and if it happens to be an Apple I'm skating on thin ice because I've been using Windows machines for a very long time. Similarly, going from a highly automated camera like the Minolta X-700 to a much older mostly manual camera with some issues takes some real gear shifting.

I do have to admit that I have one very large advantage over most of my photographer friends in that I am long past the point in life when I had to get up and go to work every weekday morning. At this point, I'm really impressed with the quality of photographic work I see from some of my younger friends while fitting it into a schedule over which they have little control for at least forty hours a week. So, I really have no very good excuse not to get things under control. Realistically, however, I'm pretty sure it is going to take some thoughtful effort to be successful.

I'm thinking one thing I can do right off is to cut back on my blog posting. One post per week is probably a practical upper limit, and once a month may be even better. Actually, that is something that may take care of itself if I just focus a bit better on thoroughness and quality in my photographic projects. Other ideas and suggestions are welcome.

Part of my problem involves the generosity of friends. Recently, I have been gifted several fine cameras and an Apple IMAC. I'm thrilled to have each of those items, but I've got to do a better job of pacing myself in taking advantage of my sudden wealth of opportunity. The IMAC, for instance, is particularly welcome as a chance to learn to use an Apple system. People occasionally ask me for help with their computers and if it happens to be an Apple I'm skating on thin ice because I've been using Windows machines for a very long time. Similarly, going from a highly automated camera like the Minolta X-700 to a much older mostly manual camera with some issues takes some real gear shifting.

I do have to admit that I have one very large advantage over most of my photographer friends in that I am long past the point in life when I had to get up and go to work every weekday morning. At this point, I'm really impressed with the quality of photographic work I see from some of my younger friends while fitting it into a schedule over which they have little control for at least forty hours a week. So, I really have no very good excuse not to get things under control. Realistically, however, I'm pretty sure it is going to take some thoughtful effort to be successful.

I'm thinking one thing I can do right off is to cut back on my blog posting. One post per week is probably a practical upper limit, and once a month may be even better. Actually, that is something that may take care of itself if I just focus a bit better on thoroughness and quality in my photographic projects. Other ideas and suggestions are welcome.

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

Why Photography?

What are people looking for in photographic images? What is it that people like about photos? What are photographers trying to communicate with their images? These questions seldom get asked explicitly, yet they lurk under every photographic presentation even though the answers are rarely articulated. It seems that there is a disconnect between visual perception and verbalization.

A possible way to approach the appeal and expression of visual imagery through photography is to look at what came before the invention of photography. Painting, drawing and sculpture are obvious precursors, but then one must ask the same question: what is the appeal in those art forms? It seems to be a tautological trap that leads nowhere. A better approach might be to look at some art forms that were in vogue immediately prior to the invention of photography which took place about 1839.

Pinhole images, camera obscura devices and cut paper shadowgraphs were available centuries before the invention of photography. Those techiques produced realistic portrayals of people and scenes from nature. What set photographic images apart from those primitive technical precursors was the persistence of a tonally complex image on a two-dimensional surface. The first instance of such an accomplishment with commercial viability was Louis Daguerre's invention of the daguerreotype process in which a light-sensitive emulsion was coated on a polished black plate on which a lens-focused image could be recorded.

Daguerre's technical breakthrough was based on earlier work by Niépce, but of equal importance was Daguerre's personal history -- he was a painter, a theatrical set designer and the co-inventor in 1822 of a theatrical presentation known as the Diorama. The Wikipedia page on the Diorama provides this description of the experience:

The objective of the Diorama was to produce an awe-inspiring illusion of reality through the use of expertly crafted paintings selectively illuminated to create a sense of movement and the passage of time. It was really more of a precursor to motion pictures than to still photography, but the technolgy to achieve that kind of fluid narrative would not be available for more than half a century. So, Daguerre's invention -extraordinary as it was - perhaps did not live up to his ambitions. But, it was a crucial step in the proliferation of both still and moving images anchored in reality.

Talbot's invention of the reproducible negative image, and then Eastman's innovations in flexible roll film and simple cameras stimlated the explosive growth of photographic imagery, which became the dominant visual experience at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. However, while the volume of photographic images hugely outpaced other visual representations, the older forms persisted and developed on their own course. Painters continued to paint, sculptors sculpted, and Dioramas were adapted to showing scenes which might otherwise be inaccessible because of time and distance constraints. Natural history museums became particularly adept at constructing Dioramas featuring animal life in natural appearing settings, including extinct species in conjectured landscapes.

People at all levels of society in the western world embraced photography as both consumers and producers of images. However, there was also a concurrent wide-spread development of Diorama forms at a popular level, often promoted by hobbyist groups such as modelers of aircraft and operators of scale model railways. In fact, today there are likely very few family homes that do not contain numerous miniature Diorama-type displays. Such displays are often rudimentary and the fabricators likely have never heard the term, "Diorama", but they clearly are related to the intent of the original Dioramas to offer a representation of reality, perhaps centered more on intensely personal experience. Glass front cabinets and tabletops contain all manner of small displays of treasured objects arranged to suggest some counterpart in real life. Doll collections, tea sets, gun collections, hunting trophies; the list is as long and wide as human experience. The intent of such displays is often to represent relationships and life experiences which are no longer directly accessible. They may also represent an effort at self definition and the construction of identity. Vernacular photography often serves those same ends.

Having practiced photography for a large part of a long life I have some favorite photographic images hanging on my walls. I also have several Diorama-type displays in cabinets and there are a couple which share space with my computers on my desk. I would say that both types of imagery serve the same purposes for me, that of representation of some percieved reality and that of construction and reinforcement of identity. The photographs are mostly depictions of family members and scenes of treasured landscapes and travel records. The Diorama-type displays are miniature, mostly symbolic, representations of identity often connected to an early and long interest in flight.

The miniature Japanese kites taped to the side of my computer remind me of building and flying kites from a hill in San Francisco. On top ot the computer is a collection of small aircraft models. My first flight experience was in the Piper Cub. Hanging on the wall above the models is a cyanotype print of a Russian reconnaissance plane from WWII housed at a museum near El Paso. To the right of my computer monitor is a fishbowl terrarium; on the top cover rests a paper model of a bi-wing amphibious aircraft, a Grumman Duck. To the casual observer that model and its placement is a quaint decoration. To me, however, the assemblage suggests a real life adventure from my youth of flying over the jungles of the northwest Amazon in just such a craft.

The whole flight obsession is related to the family hero, my uncle, who took to the skies at the age of eighteen during WWII. He flew in two more wars after that. His example, while kindling enthusiasm for the idea of the freedom of flight, proved unattainable for me in any direct way as I felt I lacked the athleticism needed for actually piloting an aircraft. However, I did find other ways to express my interest in hobbies that ultimately included photography.

The little terrarium Diorama was partly related to my uncle's example, but it was also an expression of a sought after identity as an explorer nurtured by reading many books in my childhood about Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century explorers. I did not have any real aptitude for meaningful exploration either, but I was lucky enough to survive my limited experiences in that realm and to ultimately go on to developing a more mature outlook on life's challenges and opportunities. My heroes these days tend to be artists who have helped me to see the world in new ways, and the self-description and identity I am focused on now is that of photographer.

(Watching myself go by.)

----------

Update:

I came across a post at Lenscratch featuring the work of Lori Kella who constructs elaborate paper dioramas which she then photographs. The results are unique and related to several other post-modern trends in photographic styles.

A possible way to approach the appeal and expression of visual imagery through photography is to look at what came before the invention of photography. Painting, drawing and sculpture are obvious precursors, but then one must ask the same question: what is the appeal in those art forms? It seems to be a tautological trap that leads nowhere. A better approach might be to look at some art forms that were in vogue immediately prior to the invention of photography which took place about 1839.

Pinhole images, camera obscura devices and cut paper shadowgraphs were available centuries before the invention of photography. Those techiques produced realistic portrayals of people and scenes from nature. What set photographic images apart from those primitive technical precursors was the persistence of a tonally complex image on a two-dimensional surface. The first instance of such an accomplishment with commercial viability was Louis Daguerre's invention of the daguerreotype process in which a light-sensitive emulsion was coated on a polished black plate on which a lens-focused image could be recorded.

|

| Daguerre around 1844 - Wikipedi |

The Diorama was a popular entertainment that originated in Paris in 1822....the Diorama was a theatrical experience viewed by an audience in a highly specialized theatre. As many as 350 patrons would file in to view a landscape painting that would change its appearance both subtly and dramatically. Most would stand, though limited seating was provided. The show lasted 10 to 15 minutes, after which time the entire audience (on a massive turntable) would rotate to view a second painting.

Talbot's invention of the reproducible negative image, and then Eastman's innovations in flexible roll film and simple cameras stimlated the explosive growth of photographic imagery, which became the dominant visual experience at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. However, while the volume of photographic images hugely outpaced other visual representations, the older forms persisted and developed on their own course. Painters continued to paint, sculptors sculpted, and Dioramas were adapted to showing scenes which might otherwise be inaccessible because of time and distance constraints. Natural history museums became particularly adept at constructing Dioramas featuring animal life in natural appearing settings, including extinct species in conjectured landscapes.

People at all levels of society in the western world embraced photography as both consumers and producers of images. However, there was also a concurrent wide-spread development of Diorama forms at a popular level, often promoted by hobbyist groups such as modelers of aircraft and operators of scale model railways. In fact, today there are likely very few family homes that do not contain numerous miniature Diorama-type displays. Such displays are often rudimentary and the fabricators likely have never heard the term, "Diorama", but they clearly are related to the intent of the original Dioramas to offer a representation of reality, perhaps centered more on intensely personal experience. Glass front cabinets and tabletops contain all manner of small displays of treasured objects arranged to suggest some counterpart in real life. Doll collections, tea sets, gun collections, hunting trophies; the list is as long and wide as human experience. The intent of such displays is often to represent relationships and life experiences which are no longer directly accessible. They may also represent an effort at self definition and the construction of identity. Vernacular photography often serves those same ends.

Having practiced photography for a large part of a long life I have some favorite photographic images hanging on my walls. I also have several Diorama-type displays in cabinets and there are a couple which share space with my computers on my desk. I would say that both types of imagery serve the same purposes for me, that of representation of some percieved reality and that of construction and reinforcement of identity. The photographs are mostly depictions of family members and scenes of treasured landscapes and travel records. The Diorama-type displays are miniature, mostly symbolic, representations of identity often connected to an early and long interest in flight.

The miniature Japanese kites taped to the side of my computer remind me of building and flying kites from a hill in San Francisco. On top ot the computer is a collection of small aircraft models. My first flight experience was in the Piper Cub. Hanging on the wall above the models is a cyanotype print of a Russian reconnaissance plane from WWII housed at a museum near El Paso. To the right of my computer monitor is a fishbowl terrarium; on the top cover rests a paper model of a bi-wing amphibious aircraft, a Grumman Duck. To the casual observer that model and its placement is a quaint decoration. To me, however, the assemblage suggests a real life adventure from my youth of flying over the jungles of the northwest Amazon in just such a craft.

The whole flight obsession is related to the family hero, my uncle, who took to the skies at the age of eighteen during WWII. He flew in two more wars after that. His example, while kindling enthusiasm for the idea of the freedom of flight, proved unattainable for me in any direct way as I felt I lacked the athleticism needed for actually piloting an aircraft. However, I did find other ways to express my interest in hobbies that ultimately included photography.

The little terrarium Diorama was partly related to my uncle's example, but it was also an expression of a sought after identity as an explorer nurtured by reading many books in my childhood about Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century explorers. I did not have any real aptitude for meaningful exploration either, but I was lucky enough to survive my limited experiences in that realm and to ultimately go on to developing a more mature outlook on life's challenges and opportunities. My heroes these days tend to be artists who have helped me to see the world in new ways, and the self-description and identity I am focused on now is that of photographer.

(Watching myself go by.)

----------

Update:

I came across a post at Lenscratch featuring the work of Lori Kella who constructs elaborate paper dioramas which she then photographs. The results are unique and related to several other post-modern trends in photographic styles.

Tuesday, February 05, 2019

Lynx-14

I mentioned in a recent post that I regretted not holding onto my Yashica Lynx 14. About a week later one showed up on my porch, a gift from a generous reader.

This one has an accurate and quiet shutter, smooth focusing, and a viewfinder that is a bit brighter than the one I had fifteen years ago. The meter works, but is a couple stops low and will need some attention. To enhance the contrast of the rangefinder patch I added a square of color film leader over the front window, and that makes the focusing much easier. I also added a neck strap made from a bootlace which is secured to the snap swivels with a couple hangman's knots. I loaded some Kodak ColorPlus 200 in the camera and took it for a walk to Old Town.

I shot some more with the Lynx after our monthly meeting of New Mexico Film Photographers. Margaret and I took a walk through the UNM campus and met up at the Fine Arts and Design Library with Greg Peterson who has put together a marvelous display there of Twentieth Century film cameras.

Greg follows the same policy as I in acquiring cameras for his collection -- rarely paying more than thirty or forty dollars for anything. He seems to have quite a bit more patience and perseverance in that pursuit, however, as he has turned up very fine examples of the best film cameras ever produced from all over the globe. I was particularly impressed with his medium format and large format Graflex cameras. The big single reflex press camera had a f4 Tessar that must have made marvelous images. Greg said his favorite shooter in the group was a Canon 7 rangefinder. Greg mentioned that there was a nice display of antique radios over at the Engineering Library, so I went there the next day to finish up the roll of ColorPlus with a few more low light shots.

The radios were all from the 1920s when commercial broadcasting became feasible with the widespread introduction of radio receivers. The collection included many simple crystal sets which were often built from kits, but there are also many examples of more sophisticated radio receivers from the big makers including Crosley, RCA and Western Electric.

The Yashinon-DX lens handled the dim light ok, though the florescent lamps presented a challenge for the daylight color film. I shot at f2 and 1/60. The blowup of the small label at the right edge of the image shows the good resolution of the lens at that large aperture.

I'm looking forward to doing some more low light work with the Lynx 14. Maybe I'll even get myself out on the street to shoot some night life.

This one has an accurate and quiet shutter, smooth focusing, and a viewfinder that is a bit brighter than the one I had fifteen years ago. The meter works, but is a couple stops low and will need some attention. To enhance the contrast of the rangefinder patch I added a square of color film leader over the front window, and that makes the focusing much easier. I also added a neck strap made from a bootlace which is secured to the snap swivels with a couple hangman's knots. I loaded some Kodak ColorPlus 200 in the camera and took it for a walk to Old Town.

I shot some more with the Lynx after our monthly meeting of New Mexico Film Photographers. Margaret and I took a walk through the UNM campus and met up at the Fine Arts and Design Library with Greg Peterson who has put together a marvelous display there of Twentieth Century film cameras.

Greg follows the same policy as I in acquiring cameras for his collection -- rarely paying more than thirty or forty dollars for anything. He seems to have quite a bit more patience and perseverance in that pursuit, however, as he has turned up very fine examples of the best film cameras ever produced from all over the globe. I was particularly impressed with his medium format and large format Graflex cameras. The big single reflex press camera had a f4 Tessar that must have made marvelous images. Greg said his favorite shooter in the group was a Canon 7 rangefinder. Greg mentioned that there was a nice display of antique radios over at the Engineering Library, so I went there the next day to finish up the roll of ColorPlus with a few more low light shots.

The radios were all from the 1920s when commercial broadcasting became feasible with the widespread introduction of radio receivers. The collection included many simple crystal sets which were often built from kits, but there are also many examples of more sophisticated radio receivers from the big makers including Crosley, RCA and Western Electric.

The Yashinon-DX lens handled the dim light ok, though the florescent lamps presented a challenge for the daylight color film. I shot at f2 and 1/60. The blowup of the small label at the right edge of the image shows the good resolution of the lens at that large aperture.

I'm looking forward to doing some more low light work with the Lynx 14. Maybe I'll even get myself out on the street to shoot some night life.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)