Quite a few of my old cameras require the user to estimate focal distance and to set that guess manually. For the most part, I've never found that much of a hindrance to making pictures with them, particularly in good light. Once in a while, though, in dim light and in close proximity to the subject, it is nice to have one of the little accessory rangefinders to help things along.

Of the three models I own, the tiny Voigtländer rangefinder is the most elegantly designed and crafted. The view of the image is pretty clear and contrasty, and the rotational movement of the dial is very smooth. The Voigtländer's small size adds little bulk to my pocketable cameras, and the standard-sized mount fits any camera that has an accessory shoe. I acquired this rangefinder recently from a fellow in England and it required no adjustment to the image alignment.

The vertical orientation of the Kodak rangefinder allows it to be used with cameras having tall, flip-up viewfinders, as was the case with many of the old Kodak folders. The Kodak's cast metal case has a sculpted look that harks back to the 19th Century; the round, eye-like front window seems like something Jules Verne might have dreamed up. A very nice feature of this rangefinder is a pointer and rotating circular scale that allows reading the distance setting while looking through the eyepiece. The image alignment was off when I got the rangefinder, and it proved quite a tedious job to get it working properly.

The Kodak offers a split-image view similar to what one would see through the coupled viewfinder of an Argus C3. The coincident-image featured in the other two rangefinders seems a bit easier to use, but the semi-transparent mirror coating on such instruments inevitably deteriorates over time, and the lack of image contrast becomes problematic.

The Ideal Range Finder, as it says boldly on the side of the box, was

Made in U. S. A.

FEDERAL INSTRUMENT CORP.

Long Island City, New York

The design is fundamentally functional with a black plastic case and a screw and bolt adjustment that looks like it came from the corner hardware store. As it turns out, this rangefinder offers the brightest view of the three, and is no less accurate than the Kodak or the Voigtländer. As stated in the product note folded in the box, the original buyer got a three year guarantee which included an offer to adjust the instrument if a drop caused it to lose proper alignment. The note also indicates that the user can do the readjustment by turning the set-screw on the dial. I found that to be true, though it required clamping the metal nut with channel-lock pliers and carefully exerting considerable force with a well-fitted screwdriver to turn the adjusting screw. There is no mounting bracket to fit a camera accessory shoe, though it would be easy enough to glue one in place.

Saturday, February 27, 2016

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

Exposure Meters

All of these old selenium exposure meters remain responsive to light, some more than others. The heavy, bakelite-cased Weston at the top was one of the earliest to be made available to photographers in the 1930's. The General Electric DW58 on the left, nearly as old as me, seems as sensitive to light as when it was on the dealer's shelf. The feather-weight Sekonic L-158 on the right accompanies me on every photo outing.

Match-needle operation like that on the Sekonic was a big step forward over the early meters which required first noting the light value on a scale and then transferring that value manually to the circular dials. Also, given the tiny numerals on the old meter dials, one has to assume that the early photographers were blessed with both better vision and more patience than their current-day counterparts.

None of the selenium meters I have used have been very good in low light, which is exactly when you need them most. Under normal daylight conditions they do ok, but my own guess work is usually pretty close to meter readings then. In fact, I often just take a single reading when I first step outside, and then go with my own estimates from that point onward. Given their somewhat limited range, the selenium meters might be better employed as a means for training your eye to gauge light conditions rather than as an immediate measurement tool. Still, I do feel a little more confident on photo outings with a light meter in my pocket.

For a really thorough treatment on the subject of light meters I highly recommend the web site about James Ollinger's Exposure Meter Collection. James does a great job of dealing with their history and use. The FAQ link is especially useful for new users of the old meters.

Match-needle operation like that on the Sekonic was a big step forward over the early meters which required first noting the light value on a scale and then transferring that value manually to the circular dials. Also, given the tiny numerals on the old meter dials, one has to assume that the early photographers were blessed with both better vision and more patience than their current-day counterparts.

None of the selenium meters I have used have been very good in low light, which is exactly when you need them most. Under normal daylight conditions they do ok, but my own guess work is usually pretty close to meter readings then. In fact, I often just take a single reading when I first step outside, and then go with my own estimates from that point onward. Given their somewhat limited range, the selenium meters might be better employed as a means for training your eye to gauge light conditions rather than as an immediate measurement tool. Still, I do feel a little more confident on photo outings with a light meter in my pocket.

For a really thorough treatment on the subject of light meters I highly recommend the web site about James Ollinger's Exposure Meter Collection. James does a great job of dealing with their history and use. The FAQ link is especially useful for new users of the old meters.

Friday, February 19, 2016

Camera Repair and Restoration

This list of links for camera repair was originally posted on my web site. Also see the search box in the right column for the Classic Cameras Repair Archive.

- Ace Camera Repair Index

- Camera Collecting and Restoration

- Chris's (Retina) camera pages

- Fed & Zorki Survival Site

- Flutot's Camera Repair

- Kiev Survival Site

- Kim Coxon's Pentax-Manuals.com.

(Manuals and detailed repair procedures for Pentax, Fujica, Leica, Canon, Olympus, Zorki and FSU lenses.) - Mark Hansen’s Classic Camera Repair

- Matt's Classic Camera Collection

- Micro-Tools

- Mike Elek's Cameras & Stuff

- OK photocameras: Oleg Khalyavin

(Repair of Soviet-era 35mm cameras including Zorki,FED and Kiev.

He did an excellent job of restoring the shutter of my Kiev IIa.) - Rick Oleson's Camera Stuff

- Sandeha Lynch Photography (Bellows for Isolette and other folding cameras)

- Yashica Guy

Sunday, February 14, 2016

Visual Literacy

The Museum of Modern Art is conducting a free on line course about understanding and talking about photographs, Seeing Through Photographs. The six session course uses the well-developed Coursera on line learning platform. Even highly skilled photographers often encounter difficulties in bridging the gap between vision and language. It seems like this course has a lot of potential, both for creators and consumers of photographic imagery. There is also the possibility that the quality of on line conversations about photography on blogs and web sites might be significantly elevated if enough people join in this learning opportunity. There is an article about the new MOMA course at the PetaPixel site.

Saturday, February 13, 2016

Three Women, Lost and Found

Family photos are not meant to be ephemeral or disposable; they are meant to be enduring keepsakes. Over time, however, people are careless with family photo collections. Memories fade about the people and events depicted, and a loss of meaning accompanies the loss of the people to whom the images were important. The albums and shoeboxes of snapshots end up on garage sale tables and in junkstore bins. I have looked through thousands of such photos over the past few years, but only these three have made it home with me.

A woman stands beside a new car. Who doesn't have such a picture in the family photo album? In addition to the classic subject, this one initially caught my eye because of the unusual color shift; only the car has retained something of the original color; everything else in the old Kodacolor print has faded to yellow-gray.

Turning the photo over, I found a penciled inscription noting that it was made in nearby Canutillo, Texas in 1949. And, the subject's full name was given; it was an unusual surname, and I had little trouble tracking her down on the web. She was buried in an El Paso veteran's cemetery beside her husband after a long, distinguished career as an educator. I was pleased to have rescued an image that had recorded a moment in a life of dignity and accomplishment.

There are fewer women these days appearing in public in large, funny hats, other than The Queen. Of course, at the time this portrait was made, big hats looking like heavily-frosted chocolate cakes were probably not uncommon at all. This young woman looks comfortable under her adornment, and likely quite pleased to be both where and who she is. On the back of the brown cardboard mount she has written:

Aug. 25 1898

To Papa

I like this portrait because of its very nice photographic qualities. The lighting and the tonalities seem nearly perfect. The picture appears to be in near-original condition, in part no doubt because the cardboard mount has a paper flap that covered the surface, protecting it from the bleaching effects of light and surface contamination.

People I have shown this photo to sometimes remark that the subject looks rather severe in her demeanor. To me she seems an attractive young woman, perhaps not yet beyond her teen years, and the expression to me seems enigmatic. Her dark outfit does lend a serious note to the portrait. I wonder about the limp, artificial-looking corsage; perhaps it was taken from the photographer's prop box in hopes of enlivening the composition. Surely this was some special occassion; a birthday, graduation or wedding.

A woman stands beside a new car. Who doesn't have such a picture in the family photo album? In addition to the classic subject, this one initially caught my eye because of the unusual color shift; only the car has retained something of the original color; everything else in the old Kodacolor print has faded to yellow-gray.

Turning the photo over, I found a penciled inscription noting that it was made in nearby Canutillo, Texas in 1949. And, the subject's full name was given; it was an unusual surname, and I had little trouble tracking her down on the web. She was buried in an El Paso veteran's cemetery beside her husband after a long, distinguished career as an educator. I was pleased to have rescued an image that had recorded a moment in a life of dignity and accomplishment.

There are fewer women these days appearing in public in large, funny hats, other than The Queen. Of course, at the time this portrait was made, big hats looking like heavily-frosted chocolate cakes were probably not uncommon at all. This young woman looks comfortable under her adornment, and likely quite pleased to be both where and who she is. On the back of the brown cardboard mount she has written:

Aug. 25 1898

To Papa

I like this portrait because of its very nice photographic qualities. The lighting and the tonalities seem nearly perfect. The picture appears to be in near-original condition, in part no doubt because the cardboard mount has a paper flap that covered the surface, protecting it from the bleaching effects of light and surface contamination.

People I have shown this photo to sometimes remark that the subject looks rather severe in her demeanor. To me she seems an attractive young woman, perhaps not yet beyond her teen years, and the expression to me seems enigmatic. Her dark outfit does lend a serious note to the portrait. I wonder about the limp, artificial-looking corsage; perhaps it was taken from the photographer's prop box in hopes of enlivening the composition. Surely this was some special occassion; a birthday, graduation or wedding.

Monday, February 08, 2016

Shooting the Kodak Flash Bantam

The Kodak Flash Bantam is a strut folder and one of the company's finest cameras in a line that originated from a simple design by Walter Dorwin Teague in 1935. By 1947 when the Flash Bantam appeared on the market, the shutter allowed speeds of 1/25 to 1/200 plus B and T. The four-element Anastar f4.5 lens had an anti-reflective coating and provided sharpness comparable to anything available at the time. The flip-up viewfinder is very bright and easy to use, and when folded down contributes significantly to the little camera's pocketability. The lens is fully focusable by estimation.

Kodak stopped producing 828-format film in 1985, but it is still easily possible to use the 828 cameras today, including the Kodak Bantams and the Argus M. Expired rolls of 828 film are often available on eBay and some new custom-rolled is sometimes available too. In either case, the film is a bit pricey, particularly since the little 828 rolls yield only eight exposures. Some ambitious enthusiasts cut down and re-roll 120 film to fit the 828 spools; while that nicely reproduces the original experience of using the camera, it is pretty labor intensive. A much easier alternative is to use standard 35mm film with no backing paper. The sprocket holes on the 35mm film will protrude slightly into the image, but the ease of use and increase in film length will compensate for the slight loss of image area.

The method I arrived at for using 35mm in my Flash Bantam requires two of the original 828 metal spools. I trim the protruding film leader square and tape it to one of the reels. The film is placed in a dark film changing bag and rolled onto the reel. The film is then cut loose from the cassette and taped onto the second reel, at which point it can be loaded into the camera which has had the back window previously taped to prevent exposure of the unbacked film in the camera. Advancing the film between exposures is done by rotating the winding wheel one-and-one half full turns for the first six or eight exposures, and one full turn for the remaining exposures. A 24-exposure roll of 35mm film will yield 15 to 20 frames per roll using this method. I develop and scan my own b&w film, but it is also possible to use commercial processing by putting the film back in the dark bag, taping the film end to the stub of film sticking out of the cannister and rolling it back in.

In addition to securely covering the frame window on the back of the camera, there are a couple other very simple camera modifications to the Flash Bantam which will greatly enhance the use of the camera with 35mm film, and also improve the images that will be captured by the coated Anastar lens. The little movable pawl that engages a toothed wheel allowed easy frame positioning with the original 828 film, but it is not needed and is a nuisance when loading and advancing 35mm film. To keep the pawl from slipping into the film sprocket holes you can easily introduce a small piece of foam rubber between the pawl's lever and an over-hanging tab on the camera body.

Some of my first 35mm film images from my Flash Bantam were lacking in contrast and showed a hot spot in the middle of the image. The image problem looked initially like lens flare, but the real origin was reflection at the time of exposure off the plastic framing window on the back of the camera. The simple fix was a strip of black paper cut to fit between the springs behind the pressure plate; if made the width of the camera back it will cover the shiny screw heads there as well as the reflective inner surface of the plastic window.

In shooting the Flash Bantam it is a good idea to aim a little high with the viewfinder in order to properly center the image between the film's sprocket holes.

My Flash Bantam needed just some cleaning of the lenses and a little squirt of electrical contact cleaner into the shutter to get it working properly. An excellent tutorial on Flash Bantam shutter repair can be found at the Camera Collecting and Restoration site.

A manual for the very similar Bantam 4.5 can be found at the Butkus site.

Numerous examples of images made with the Flash Bantam are available on the blog.

Kodak stopped producing 828-format film in 1985, but it is still easily possible to use the 828 cameras today, including the Kodak Bantams and the Argus M. Expired rolls of 828 film are often available on eBay and some new custom-rolled is sometimes available too. In either case, the film is a bit pricey, particularly since the little 828 rolls yield only eight exposures. Some ambitious enthusiasts cut down and re-roll 120 film to fit the 828 spools; while that nicely reproduces the original experience of using the camera, it is pretty labor intensive. A much easier alternative is to use standard 35mm film with no backing paper. The sprocket holes on the 35mm film will protrude slightly into the image, but the ease of use and increase in film length will compensate for the slight loss of image area.

The method I arrived at for using 35mm in my Flash Bantam requires two of the original 828 metal spools. I trim the protruding film leader square and tape it to one of the reels. The film is placed in a dark film changing bag and rolled onto the reel. The film is then cut loose from the cassette and taped onto the second reel, at which point it can be loaded into the camera which has had the back window previously taped to prevent exposure of the unbacked film in the camera. Advancing the film between exposures is done by rotating the winding wheel one-and-one half full turns for the first six or eight exposures, and one full turn for the remaining exposures. A 24-exposure roll of 35mm film will yield 15 to 20 frames per roll using this method. I develop and scan my own b&w film, but it is also possible to use commercial processing by putting the film back in the dark bag, taping the film end to the stub of film sticking out of the cannister and rolling it back in.

In addition to securely covering the frame window on the back of the camera, there are a couple other very simple camera modifications to the Flash Bantam which will greatly enhance the use of the camera with 35mm film, and also improve the images that will be captured by the coated Anastar lens. The little movable pawl that engages a toothed wheel allowed easy frame positioning with the original 828 film, but it is not needed and is a nuisance when loading and advancing 35mm film. To keep the pawl from slipping into the film sprocket holes you can easily introduce a small piece of foam rubber between the pawl's lever and an over-hanging tab on the camera body.

Some of my first 35mm film images from my Flash Bantam were lacking in contrast and showed a hot spot in the middle of the image. The image problem looked initially like lens flare, but the real origin was reflection at the time of exposure off the plastic framing window on the back of the camera. The simple fix was a strip of black paper cut to fit between the springs behind the pressure plate; if made the width of the camera back it will cover the shiny screw heads there as well as the reflective inner surface of the plastic window.

In shooting the Flash Bantam it is a good idea to aim a little high with the viewfinder in order to properly center the image between the film's sprocket holes.

My Flash Bantam needed just some cleaning of the lenses and a little squirt of electrical contact cleaner into the shutter to get it working properly. An excellent tutorial on Flash Bantam shutter repair can be found at the Camera Collecting and Restoration site.

A manual for the very similar Bantam 4.5 can be found at the Butkus site.

Numerous examples of images made with the Flash Bantam are available on the blog.

Wednesday, February 03, 2016

Don't miss these on line exhibits

|

| Seventh Avenue | Berenice Abbott |

Berenice Abbott's great portrait of fast changing NYC (in The Week)

Moving Freely, and Photographing in Marseille

Joan Liftin's street photography (in The NY Times)

These are two terrific photographers of the urban scene who are polar opposites in terms of technique. Abbott's expansive, minutely detailed views of The City were made with a large format camera, often from precarious heights. Liftin works fast and close to capture movement and emotion with the nimbleness of a modern dancer.

Friday, January 29, 2016

A couple more pinholes

I took the pinhole for a walk through the Piedras Marcadas rock art site on the west side of Albuquerque. I was pleased with the pictures, though I don't know that I'll find a use for them in my current book project.

I had a great walk. The sun was warm enough to make me regret wearing a winter coat. Half way to the bear shaman glyph I was greeted by a coyote chorus. Also saw lots of birds: road runners, doves and rock wrens.

I like the pinhole camera for the way its pictures reflect my feelings as I stand in front of the work of the ancient image makers. I always have the sensation in such places that the great expanse of time since the images were made is really part of an unbroken continuum in which those original artists and I somehow exist simultaneously.

I had a great walk. The sun was warm enough to make me regret wearing a winter coat. Half way to the bear shaman glyph I was greeted by a coyote chorus. Also saw lots of birds: road runners, doves and rock wrens.

I like the pinhole camera for the way its pictures reflect my feelings as I stand in front of the work of the ancient image makers. I always have the sensation in such places that the great expanse of time since the images were made is really part of an unbroken continuum in which those original artists and I somehow exist simultaneously.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Albuquerque On Wheels

I took my pinhole camera for a walk in the neighborhood. It is the first time I've shot b&w in nearly a year. I had to go back and read the directions on processing. There were some odd looking clumps of stuff floating around in my year-old hc-110 developer, but it seems to be working ok.

I'm getting together some ideas for another book, this time about pinhole photography. I don't really need more pinhole pictures as I've got at least a year's worth of images, but I did need to get in touch with the process again. I learned some things about book making from my last experience, and I'm looking forward to trying out some new tools in the next round.

I'm getting together some ideas for another book, this time about pinhole photography. I don't really need more pinhole pictures as I've got at least a year's worth of images, but I did need to get in touch with the process again. I learned some things about book making from my last experience, and I'm looking forward to trying out some new tools in the next round.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

The Book

I have completed the process of creating a photo book using Blurb's BookWright application. I uploaded my efforts to the Blurb site and received the proof copy about two weeks later. It all looked pretty good, but I decided to adjust the contrast in a few of the pictures and corrected a couple errors in the text. I resubmitted the material and ordered three copies for my own use, along with a pdf which I will redistribute myself. The book is now listed in the Blurb bookstore where it can be previewed and purchased.

I have no complaints about the quality of the results I got from Blurb. The images look as good to me as what I could do myself on a good quality inkjet. The layout and design seems exactly as I specified. Most importantly, as a newcomer to self-publishing, I think the Blurb experience provided a very good basic introduction to the process of book design.

Where Blurb comes up short in my opinion is in regard to economic feasibility. Going much beyond the 32 pages of the book I produced results in a product that will be priced beyond what I think most people are prepared to pay for a photo book. I think a book of the size I made could be used effectively as an exhibit catalog, and that is actually something I had in mind in its creation. For something more substantial I think I would look to other possibilities.

I have put together a page on my book on my blog with a link to the Blurb bookstore. I also made the pdf ebook available on the page which contains all the text and illustrations of the hardcopy at a cost of five dollars. However, for the remainder of the month of January I will email a copy to anyone interested at no charge. I would suggest that people wanting the pdf contact me directly by email rather than posting a message in the blog comments. My email address is mike dot connealy at gmail dot com.

The pdf file of the book is viewable on any device, though big screens are going to be a better choice. Web browsers can handle pdf display, but a dedicated viewer like Adobe Acrobat Reader will do a better job of displaying two pages simultaneously as the book was designed to be viewed; there is one double-page photo spread where that is particularly desirable.

I have no complaints about the quality of the results I got from Blurb. The images look as good to me as what I could do myself on a good quality inkjet. The layout and design seems exactly as I specified. Most importantly, as a newcomer to self-publishing, I think the Blurb experience provided a very good basic introduction to the process of book design.

Where Blurb comes up short in my opinion is in regard to economic feasibility. Going much beyond the 32 pages of the book I produced results in a product that will be priced beyond what I think most people are prepared to pay for a photo book. I think a book of the size I made could be used effectively as an exhibit catalog, and that is actually something I had in mind in its creation. For something more substantial I think I would look to other possibilities.

I have put together a page on my book on my blog with a link to the Blurb bookstore. I also made the pdf ebook available on the page which contains all the text and illustrations of the hardcopy at a cost of five dollars. However, for the remainder of the month of January I will email a copy to anyone interested at no charge. I would suggest that people wanting the pdf contact me directly by email rather than posting a message in the blog comments. My email address is mike dot connealy at gmail dot com.

The pdf file of the book is viewable on any device, though big screens are going to be a better choice. Web browsers can handle pdf display, but a dedicated viewer like Adobe Acrobat Reader will do a better job of displaying two pages simultaneously as the book was designed to be viewed; there is one double-page photo spread where that is particularly desirable.

Sunday, January 17, 2016

Your Lens

I posted this article originally on my web site because it gives such a good explanation of the complete process for making lenses. The article by Walter E. Burton was published in the Aug. 1939 issue of Popular Photography.

I made the copy using my digital camera as it is contained in a bound copy of the issues from July of that year. There is some distortion as a result due to curvature of the pages.

The photos that accompanied the story are at the bottom of the article; click on them to display at full size.

Labels:

Aug 1939,

Bausch and Lomb,

Lens Making,

Popular Photography,

Wollensak

Friday, January 15, 2016

Agfa Synchro Box

A friend gave me this pretty Agfa Synchro Box just after I had decided to go on a nearly year-long sabbatical from photography. So, it has taken me much longer than it should have to get some pictures from the camera. This '50s box resembles the earlier Agfa Shur Flash, but the case and the inner cone are all metal and the front plate sports a natty deco design. As the name implies, the camera has a couple contacts on the top deck for attaching an accessory flash. It also has two aperture settings, a built-in yellow filter, a tab which permits a choice of instant or time exposures, and both tripod and cable release sockets. The viewfinder windows are small, but bright.

The Synchro Box yields 8 frames from standard 120 roll film which is still easy to find on line. I shot two rolls of Lomography 100 color film in the camera. One roll was used mostly on a trip to Phoenix, the other on a morning walk through the Albuquerque Botanical Gardens. I like the results from the film just fine, but the gray numerals on black backing paper present a real challenge to read through the ruby window. The only way I could see the frame numbering was to hold the back of the camera so that the sun shone directly on it. I hate doing that as there is always a risk that some light will bleed through or around the paper backing.

The adjustable aperture does add some adaptability to different lighting conditions, but I selected scenes that would allow using the smaller f16 setting as I felt that would likely give me sharper results and better depth of field.

A manual for the Agfa Synchro Box is available on line at the Butkus web site.

Albuquerque has been getting different weather every day lately, not unlike much of the rest of the country, I guess.

For most of the pictures on the second roll through the camera I used a Kodak No.13 accessory close-up lens which is a perfect fit to the Agfa lens ring. That lets the camera get within nice portrait range of about 3.5 feet, and I think it also adds a bit of sharpness to the resulting images. The little garden sculpture which is a favorite test subject compares nicely to other camera images I have made at the garden.

The wagon wheel in the garden's demonstration farm yielded the sharpest result in my close-up series. Some of the other shots were a bit fuzzy, either because I misjudged the distance, or perhaps because I didn't have the accessory lens seated quite properly.

I was surprised to come across this porcupine enjoying a breakfast of low-hanging tree twigs near the entrance to the Japanese Garden. He stood still for his portrait, but didn't look particularly happy about the opportunity, and the shot is not a very good likeness. Still, it was nice to get a chance to do a bit of nature photography with a box camera.

The Synchro Box yields 8 frames from standard 120 roll film which is still easy to find on line. I shot two rolls of Lomography 100 color film in the camera. One roll was used mostly on a trip to Phoenix, the other on a morning walk through the Albuquerque Botanical Gardens. I like the results from the film just fine, but the gray numerals on black backing paper present a real challenge to read through the ruby window. The only way I could see the frame numbering was to hold the back of the camera so that the sun shone directly on it. I hate doing that as there is always a risk that some light will bleed through or around the paper backing.

The adjustable aperture does add some adaptability to different lighting conditions, but I selected scenes that would allow using the smaller f16 setting as I felt that would likely give me sharper results and better depth of field.

A manual for the Agfa Synchro Box is available on line at the Butkus web site.

Albuquerque has been getting different weather every day lately, not unlike much of the rest of the country, I guess.

For most of the pictures on the second roll through the camera I used a Kodak No.13 accessory close-up lens which is a perfect fit to the Agfa lens ring. That lets the camera get within nice portrait range of about 3.5 feet, and I think it also adds a bit of sharpness to the resulting images. The little garden sculpture which is a favorite test subject compares nicely to other camera images I have made at the garden.

The wagon wheel in the garden's demonstration farm yielded the sharpest result in my close-up series. Some of the other shots were a bit fuzzy, either because I misjudged the distance, or perhaps because I didn't have the accessory lens seated quite properly.

I was surprised to come across this porcupine enjoying a breakfast of low-hanging tree twigs near the entrance to the Japanese Garden. He stood still for his portrait, but didn't look particularly happy about the opportunity, and the shot is not a very good likeness. Still, it was nice to get a chance to do a bit of nature photography with a box camera.

Labels:

Agfa Synchro Box,

Albuquerque,

box camera,

Lomography 100,

Phoenix,

Unicolor C-41

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

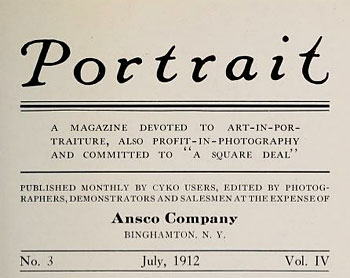

Portrait...

Ansco published a magazine entitled Portrait from 1909 to 1921

to promote its photographic products, particularly the Cyco line of

photo printing paper. Ansco's magazine targeted advanced amateurs and

professional studio portraitists. Articles dealt with aesthetic and

technical topics of interest to those groups, as well as effective

marketing strategies. The publication's cover photo often featured a

prominent portrait photographer, and an article was devoted to the

photographer's work along with a brief biography. Articles on aesthetics

and technique were frequently the work of prominent critic, Sadakichi

Hartmann. Many issues of Portrait are available on line at the Internet Archive site, and a good overview of the publication has been prepared by Gary D. Saretzky.

The cover of the July,1912 issue of Portrait featured Gertrude Kasebier, one of the original founders of the Photo-Secession movement along with Alfred Stieglitz. Examples of Kasebier's work had appeared in the first issue of Camera Work in 1903, and Stieglitz again paid tribute to her extraordinary talent in the April,1905 issue. The two parted company around the time this article appeared in Ansco's magazine. Stieglitz accused Kasebier of putting commercial considerations above the aesthetic ideals of the Photo Secession, and Kasebier left the organization.

The 1912 Ansco article had a fawning tone and the portrait that was included as an example of her work had a rather bland character which seems to give some weight to Stieglitz's assertions. Taking a broader view of Kasebier's long and productive career, however, makes Stieglitz's judgment seem short-sighted and uncharitable. Still, it is interesting to compare some of her commercial portraiture with the kind of pictures that first brought her to the pages of Camera Work.

The cover of the July,1912 issue of Portrait featured Gertrude Kasebier, one of the original founders of the Photo-Secession movement along with Alfred Stieglitz. Examples of Kasebier's work had appeared in the first issue of Camera Work in 1903, and Stieglitz again paid tribute to her extraordinary talent in the April,1905 issue. The two parted company around the time this article appeared in Ansco's magazine. Stieglitz accused Kasebier of putting commercial considerations above the aesthetic ideals of the Photo Secession, and Kasebier left the organization.

The 1912 Ansco article had a fawning tone and the portrait that was included as an example of her work had a rather bland character which seems to give some weight to Stieglitz's assertions. Taking a broader view of Kasebier's long and productive career, however, makes Stieglitz's judgment seem short-sighted and uncharitable. Still, it is interesting to compare some of her commercial portraiture with the kind of pictures that first brought her to the pages of Camera Work.

This portrait of Evelyn Nesbit by Kasebier was made about 1900 and published as a photogravure in the first issue of Camera Work in 1903.

Labels:

Alfred Stieglitz,

Ansco,

Camera Work,

Gertrude Kasebier,

Photo-Secession,

Portrait

Friday, January 08, 2016

Phase One

I uploaded a proof copy of my publication to Blurb yesterday. The 30-page softcover in magazine format was put together with Blurb's BookWright application. For free software, I thought BookWright was really pretty nice in that it lets you combine text and pictures easily and provides what looks to be a good approximation of what the published document will look like. There were a few small glitches and bugs in the process, but it is clear from reading on line chatter about the program that it has undergone a very rapid period of development in which a large number of the complaints of users have been responded to. My guess is that my own comments here are going to be dated very quickly.

The documentation for some features is a little sketchy, but most of that is taken care of by a bit of experience in using the program. For instance, I had a little trouble discerning at first how to save my images in PhotoShop in a form that would be acceptable for printing. Getting the images and text boxes lined up properly was a little challenging as there is no snap-to function and the grid display is not very helpful. While there are a large number of fonts available, there is not a very good way of establishing a user-chosen default, and I found I had to keep checking to make sure the program was using the choice I preferred. None of these issues was a deal breaker, however, and I think one is likely to face similar problems with about any software package of this type.

The question that remains unanswered for me is whether or not the Blurb final product is going to meet my expectations in regard to quality and cost. I thought I might get some idea about those issues by looking at examples in the on line store where users' publications are shown. It turns out however that somewhere in the neighborhood of 99% of the Blurb self-publishers don't seem to have a clue about making books. Most of the photo book offerings lack any clear message and often seem to be rather randomly assembled collections of pictures, usually with no textual context. Prices for hardcopy books very often exceed $100, which is way, way beyond what I would be willing to pay, even for something very well produced and by a known artist.

So, I am relying at this point mostly on my own experience and perceptions for evaluating the Blurb possibilities. I decided to keep costs in check by selecting the better quality magazine format and limiting the page count. I was pleased to see that I could produce a publication that presented some coherent ideas at a base cost of under ten bucks. However, when I placed the order for my proof copy I was shocked to see that the shipping charge for that single issue was over six dollars. That, for me, makes the total cost just barely acceptable. As it turns out, you can get up to five issues of the publication shipped for the same amount, but I'm not sure that really offers me anything useful.

My impression at this point is that the most practical outcome of my Blurb efforts will be some kind of ebook, probably in pdf format. That could be made available on line, and the production cost is neglibible. I will probably put together a package of options including hardcover offerings, but my expectations at this point fall quite a bit short of the self-publishing hype that presently saturates the web.

The documentation for some features is a little sketchy, but most of that is taken care of by a bit of experience in using the program. For instance, I had a little trouble discerning at first how to save my images in PhotoShop in a form that would be acceptable for printing. Getting the images and text boxes lined up properly was a little challenging as there is no snap-to function and the grid display is not very helpful. While there are a large number of fonts available, there is not a very good way of establishing a user-chosen default, and I found I had to keep checking to make sure the program was using the choice I preferred. None of these issues was a deal breaker, however, and I think one is likely to face similar problems with about any software package of this type.

The question that remains unanswered for me is whether or not the Blurb final product is going to meet my expectations in regard to quality and cost. I thought I might get some idea about those issues by looking at examples in the on line store where users' publications are shown. It turns out however that somewhere in the neighborhood of 99% of the Blurb self-publishers don't seem to have a clue about making books. Most of the photo book offerings lack any clear message and often seem to be rather randomly assembled collections of pictures, usually with no textual context. Prices for hardcopy books very often exceed $100, which is way, way beyond what I would be willing to pay, even for something very well produced and by a known artist.

So, I am relying at this point mostly on my own experience and perceptions for evaluating the Blurb possibilities. I decided to keep costs in check by selecting the better quality magazine format and limiting the page count. I was pleased to see that I could produce a publication that presented some coherent ideas at a base cost of under ten bucks. However, when I placed the order for my proof copy I was shocked to see that the shipping charge for that single issue was over six dollars. That, for me, makes the total cost just barely acceptable. As it turns out, you can get up to five issues of the publication shipped for the same amount, but I'm not sure that really offers me anything useful.

My impression at this point is that the most practical outcome of my Blurb efforts will be some kind of ebook, probably in pdf format. That could be made available on line, and the production cost is neglibible. I will probably put together a package of options including hardcover offerings, but my expectations at this point fall quite a bit short of the self-publishing hype that presently saturates the web.

Monday, January 04, 2016

Better Photos

Sears Roebuck & Co., in the early

years of the Twentieth Century, may have been Kodak's stiffest domestic

competitor in the marketing of photographic technology and services.

The mail order company's giant catalog had a large section devoted to

cameras and darkroom equipment. The items sold were from domestic and

imported sources, and were similar to Kodak's offerings in regard to

features, quality and pricing. Sears imported some high quality cameras

from Germany including models from ICA A.G. which became a part of the

Zeiss Ikon conglomerate in 1926. At the lower end of the consumer

scale, Sears relied initially on cameras from the Conley Camera Co. of

Rochester, Minn, which were sometimes marketed under the "Seroco" label.

Sears and Kodak competed for the affections of amateur photographers with magazines published monthly and sold for five cents a copy. Both publications, appearing first in 1913, were twenty-five or thirty pages in length and very similar in regard to design, layout and subject matter. The Kodak offering, KODAKERY, was published at the company headquarters in Rochester, NY and had somewhat of an edge over Sears' Better Photos in terms of design style, as well as in the quality of the typography and photo reproductions. Articles in both magazines focused on photo technique and photo subjects of concern to the amateur audience including hints on making portraits of family members, children and pets, along with sports, landscape and snow scenes. Sears offered film and plate processing from its Chicago headquarters, as well as the making of prints and enlargements; an 8x10 could be had for fifteen cents, and for another six cents, you could have it mounted.

Until "miniature" 35mm cameras started to get popular in the mid 1920's, most consumers were content to get their snapshots made into contact prints. While Sears and other companies offered enlarging services, few amateurs in the first decades of the Century would have had the capability of making their own enlargements. For the advanced amateurs with adequate finances or mechanical skills, however, there were options available. An article in the Vol.1, No.2 issue of Better Photos illustrated a method for using a folding camera as an enlarger for making prints from glass plate negatives. Mounting the contraption on a window with a light-gathering mirror was probably a very practical idea at a time when electric lighting still had limited availability.

The editorial staff of Better Photos also conducted a twelve-lesson Correspondence School of Photography which was often advertised on the inside front cover of the magazine. The ad ended with the assurance that

Sears and Kodak competed for the affections of amateur photographers with magazines published monthly and sold for five cents a copy. Both publications, appearing first in 1913, were twenty-five or thirty pages in length and very similar in regard to design, layout and subject matter. The Kodak offering, KODAKERY, was published at the company headquarters in Rochester, NY and had somewhat of an edge over Sears' Better Photos in terms of design style, as well as in the quality of the typography and photo reproductions. Articles in both magazines focused on photo technique and photo subjects of concern to the amateur audience including hints on making portraits of family members, children and pets, along with sports, landscape and snow scenes. Sears offered film and plate processing from its Chicago headquarters, as well as the making of prints and enlargements; an 8x10 could be had for fifteen cents, and for another six cents, you could have it mounted.

Until "miniature" 35mm cameras started to get popular in the mid 1920's, most consumers were content to get their snapshots made into contact prints. While Sears and other companies offered enlarging services, few amateurs in the first decades of the Century would have had the capability of making their own enlargements. For the advanced amateurs with adequate finances or mechanical skills, however, there were options available. An article in the Vol.1, No.2 issue of Better Photos illustrated a method for using a folding camera as an enlarger for making prints from glass plate negatives. Mounting the contraption on a window with a light-gathering mirror was probably a very practical idea at a time when electric lighting still had limited availability.

The editorial staff of Better Photos also conducted a twelve-lesson Correspondence School of Photography which was often advertised on the inside front cover of the magazine. The ad ended with the assurance that

"The student will not be hurried nor urged to complete the course in less time than is necessary to secure a thorough knowledge of the principles of photography, and lessons may be returned for criticism and correction as many times as the student desires, or until proficiency is attained."The price for all of that was $3.00. Even after applying the 20x factor for inflation since 1913, it seems a pretty good deal.

The range of prices for cameras adjusted for inflation seems very

similar to what is offered to consumers today. In 1913, box cameras

sold for the equivalent of about $40 in today's inflated dollars.

Domestic folders with faster lenses and multi-speed shutters went for

about $200, while top-of-the-line imports sold for around $1000 in

current dollar value.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)