Becoming familiar with the operation of the

Univex Mercury II got me looking into the history of the rotary shutter in photography. It is a shutter type that has been common since photography's very early days and there is a lot on the web about it. I'm just going to summarize some of my more interesting web finds here with links to the sources.

Most box cameras are equipped with rotary shutters; they are simple and extremely reliable, and give an exposure time of 1/30-1/60 second. Here is an illustration of the shutter in my Kodak Brownie Hawkeye Flash; the shutter is held open with the "B" setting to give a clear view of the parts.

The round black hole is the aperture allowing light into the lens. When the shutter release is activated, the cover paddle is lifted and the kidney-shaped opening in the circular shutter plate rotates past the aperture, with the time of its passage being determined by the spring tension and the length of the kidney-shaped hole. At the end of the cycle, the paddle flips back down to cover the opening and the shutter disk rotates back to the starting position.

I picked up an old windup Kodak motion picture camera in the 1960s. Even though it was about 30 years old when I got it, the camera ran very smoothly. I didn't give the mechanics of it much thought at the time, but it very likely had a rotary shutter like all the mechanical movie cameras of the time.

The rotating shutter mechanism in a modern sound-synched movie camera is usually a half circle set to operate at 24 frames per second and giving an exposure to each frame of about 1/50 second. The purpose of this timing is not only to achieve the correct exposure, but also to yield the illusion of smooth, natural movement when the images are projected. The animated gif below from Wikipedia illustrates the action of the motion picture shutter; the film is advanced one frame during the closed phase of each rotation.

|

| Joram van Hartingsveldt |

Perhaps inspired by motion picture technology, Heinz Kilfitt designed the Robot, a 35 mm motorized-advance still camera in about 1930. A very nice article about this long-lived precision camera is at the

Dieselpunks site.

By locating the shutter just behind the lens, Kilfitt was able to achieve a very compact camera design that gave a relatively large, square image measuring 24x24 mm.

"The rotary shutter and the film drive are like those used in cine cameras. When the shutter release is pressed, a light-blocking shield lifts and the shutter disc rotates a full turn exposing the film through its open sector; when the pressure is released the light-blocking shield returns to its position behind the lens, and the spring motor advances the film and recocks the shutter. This is almost instantaneous. With practice a photographer could take 4 or 5 pictures a second. Each winding of the spring motor was good for about 25 pictures, half a roll of film. Shutter speed was determined by spring tension and mechanical delay since the exposure sector was fixed. The Robot I had an exposure range of 1 to 1/500 s plus the usual provision for time exposures."

The rotary shutter reached an apex of sophistication in 1963 when Olympus introduced the Olympus-Pen F, a half-frame single lens reflex design by Yoshihisa Maitani.

|

| Wikipedia |

It seems remarkable that Maitani could fit a focal plane rotary shutter and a Poro prism slr viewfinder into a camera of such diminutive size. Much of the success of the effort was due to the development of an exceedingly thin and lightweight titanium shutter disk which allowed a top speed of 1/500 second.

|

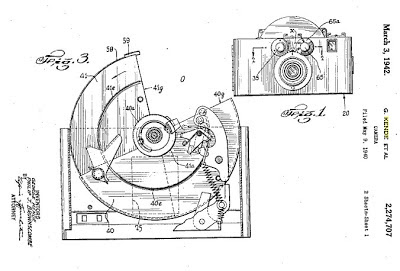

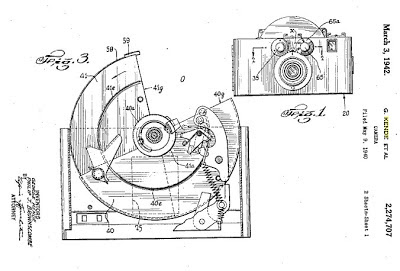

| U.S. Patent Office |

In some ways the Universal Camera Corporation Mercury camera was even more remarkable than the earlier Robot and the later Pen F. The large diameter focal plane shutter devised by George Kende was extremely robust and accurate, achieving a reliable top speed of 1/1000 second. The relative simplicity of the shutter design facilitated low-cost construction and made the Mercury much more likely to be successfully repaired and renovated by the DIY enthusiast.

|

| U.S. Patent Office |

The shutter in my Mercury II was sluggish when I received it. A little lighter fluid applied with a small brush was all that was needed to bring it back to life, and the resultant pictures show it to be operating as designed.