The early Kodak Brownie folding cameras are very capable shooters, but one doesn't see many pictures made with them, even by vintage camera enthusiasts. I think this is probably due mostly to a design style that today seems very quaint. In fact, however, the camera's design is highly functional. The Brownie is one of the most compact medium-format cameras ever built; folded up, it easily slips into a pocket. Features include variable aperture and shutter settings, standard tripod mounts for vertical and horizontal orientation, a cable release socket, and variable focus.

The swiveling reflex finder is unmagnified and a challenge to use; for that reason, I have added an eye-level finder to mine from an newer junker. A great virtue of the No.2 Kodaks is that they all take currently available 120 roll film, so there is no need for any modifications of film reels or cameras. Because modern films are a good deal faster than those of the early 20th Century, it is a good idea to keep a flap of black tape over the ruby window on the back.

My camera is a zone-focus model, the distance being set by drawing out the bellows to lock at one of three settings marked in feet as 100, FIXED, and 8. My guess would be that the "Fixed" setting is equal to about 25 feet; in good light and at the smaller f-stops, that will produce good results over a range of distances from a lens that has a focal length of 90-100 mm. It is a good idea to create a depth of field chart using one of the on line calculators in order to achieve good focus under a variety of conditions.

The front of the shutter housing is cluttered with a wordy jumble of lighting condition descriptors and suggestions for shutter speed settings. All of that can be safely ignored. The aperture settings are marked with "Universal System" values. That means that the 16 is the same as f-16 in the current-day system, but the values below and above are just numerically halved or doubled. So, while the scale on the Brownie shows values of 8,16,32 and 64, the actual exposure values corresponding to what would be indicated by a modern exposure meter are 11,16,22 and 32. That sounds more confusing than it is in practice. Just bear in mind that going a stop wider doubles the exposure, while a stop narrower halves the light getting to the film.

The ball bearing shutter is quite reliable and smooth in operation, but I generally like to use a cable release with mine even when hand-holding the camera in order to reduce blur-inducing movement. Better yet for stationary subjects, putting the camera on a tripod is always good insurance for the sharpest possible images, particularly for exposures less than the 1/50 second maximum speed. For low light, indoor shots, I generally find I can estimate exposure time adequately from about a half second and slower, and selecting a small aperture produces good depth of focus.

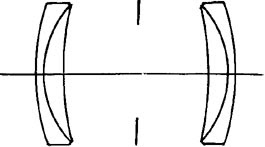

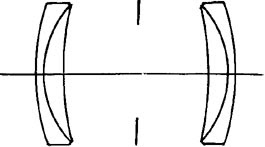

With some care given to technique as described above, the folding Brownies can deliver wonderful images. The big 6x9 centimeter negatives will yield an astonishning range of tonal values, and the lenses are capable of surprising sharpness with little distortion or aberration. Kodak sold the No.2 Folding Brownies in 1917 for $6.00 equipped with a single meniscus achromatic lens located behind the aperture. For a dollar-and-a-half more you could get the Rapid Rectilinear lens which had two elements symmetrically arranged fore and aft of the aperture. Since most users at the time would have been looking to get contact prints, the meniscus lens was fully adequate in terms of sharpness, and it will even support considerable enlargement. The Rapid Rectilinear design can produce image sharpenss rivaling much more modern and costly lenses; it was the choice of many of the great classic era photographers including Stieglitz, Steichen, Weston and Cunningham.

The Rapid Rectilinear Lens