|

| Argus A2F |

The Argus A, introduced in 1936, was the first American-made camera to use the the standard 35mm film cartridge. The A2F, in production from 1939 to 1941, featured some additions to to the basic model A including a top-deck extinction meter with an exposure calculator. Shutter speeds ran from 1/25 seconds to 1/200 seconds, plus B and T. The 3-element Anastigmat lens had aperture settings from f4.5 to f18, and it sat on a full-focusing mount that allowed a minimum focal distance of 15 inches(!) Though it lacked flash-sync, the A2F was the most feature-rich and capable member of the Argus A line which continued on into the the 1950s.

In the 1930s, Leica was the standard setter. It doesn't take much imagination to see that the Leitz cameras were the primary inspiration behind the the original Argus A. In fact, Leica-copies of varying degrees of fidelity appeared in many national guises. The most notable Leica-like cameras were made in the Soviet Union in vast numbers over a period of decades. It is interesting to compare the efforts in the U.S. and the Soviet Union to appropriate the Leica mystique. The Soviet response was driven by ideology and resulted in copies that were very faithful to the original German design and of quite good quality. Given the huge production and the somewhat inferior materials and workmanship, it is tempting to assume that the Soviet cameras were produced at a low cost compared to the Barnack originals. But, how does one make that determination in an economy that is totally State-run?

In the free-market economy of the U.S., costs, competition and demand were clearly the drivers of production, and the result from Argus (then, the International Radio Corp.) was a camera of more modest aspirations that resembled the Barnack Leicas only in rather broad terms. Charles Verschoor, the IRC president, avoided the mistake made by a number of other American industrialists of going head to head with the European camera makers who followed a tradition of ultra-high quality production aimed at satisfying the needs of a wealthy elite. Instead, the Argus A was conceived from the beginning as a product that would be widely accessible to middle-class photo enthusiasts, even in the midst of the world-wide Depression.

Verschoor made good use of previous production and marketing experience acquired in the making of low-cost radio sets. The cheap bakelite plastic cases of the radios provided a useful model for camera body construction using a proven, mature technology. Mass marketing acumen was clearly demonstrated in the choice to publicize the debut of the Argus A in the first issue of Life Magazine. Of course, making and marketing a cheap camera is one thing, while making a profit selling a good, cheap camera is quite another.

Verschoor's entrepreneurial genius was evident in his choice of a chief designer capable of finding just the right balance between frugality and quality. Gustave Fassin was a designer of precision optical instruments who had learned his craft in Belgium where he taught at the Technical School of Ghent and had charge of workshops in the Societe Belge d'Optique before emigrating to the U.S. in the 1920s. Fassin took up residence in the capital of the U.S. photographic world, Rochester, NY, and taught at the University of Rochester Institute of Applied Optics. Fassin also worked for both of the giants of the photo world based in Rochester, Kodak and the Bausch & Lomb Company.

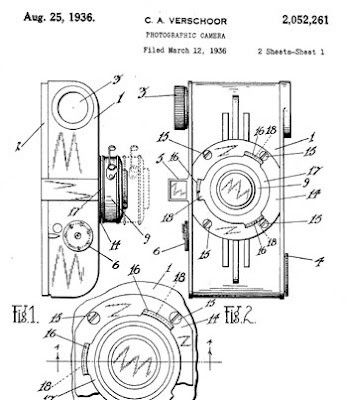

By the mid-1930s, Fassin held an impressive number of patents for optical devices, and he also clearly made good use of opportunities to learn about resources and production techniques that the big U.S. companies used to succeed in a very competitive industry. Although the patent application for the Argus A bears only Verschoor's name, the design similarities with the later Argus C3 carrying only Fassin's name shows that the first Argus was the Belgian's design. At the same time, there is little doubt about the importance of Verschoor's abilities to read the market and to marshal resources in making it possible to produce a pretty good miniature camera that cost one-fifth the price of Kodak Retina, and one tenth that of the Leica A with essentially the same basic features. The Fassin design even surpassed the high-priced competition in a couple respects, including the removable back that made film loading a snap compared to the Leica, and neither Kodak nor Leitz standard lenses provided the kind of extreme close-up capability of the Argus f4.5 Anastigmat on the AF in 1937 and A2F in 1939.

In truth, the Leitz company leadership quite likely lost little if any sleep over the pretender from Ann Arbor. The Leica was never aimed at the kind of market that Argus captured, and in Europe Argus cameras were virtually unknown. Kodak's reaction to the competition from the Argus was more complicated. The Kodak 35 and the Kodak 35 Rangefinder cameras seem clearly to have been designed in response to the quickly building popularity of the Argus A, and later the C3. The domestically produced Kodaks featured some superior lens opitions and they sold reasonably well, but they didn't come close to achieving the popularity of the Argus cameras, and somehow Kodak never really caught up. Perhaps the company didn't try as hard as it might have to quash the competition. Kodak,after all, was more of a film producer than a camera manufacturer. In the U.S., Kodak's film manufacturing, distributing and processing capabilities gave it a market dominance similar to what Microsoft enjoys today. What that meant in terms of practical economics was that nearly every time an amateur photographer pressed the shutter release of an Argus A or C3, it was money in the bank for Kodak .

The compact simplicity of the Argus A2F is very appealing to me. The appearance and over-all ergonomics seem to me to be superior to the later and more popular C3. I don't mind the lack of double-exposure prevention, I like the self-cocking shutter, and the close-focusing capability of the camera makes it hard to beat in regard to versatility. The lens is adequately sharp, with no obvious spherical aberration. Being a pre-war design, there is no anti-glare coating on the lens surfaces. Images from the Argus tend to be a little soft around the margins. Images from the camera show a slight amount of corner vignetting, probably caused by the shadow of the large coil spring that held the lens in the open position. The focus ring of the A2F is a little difficult to get at and tends to slow shooting a bit as a result. I'm not sure what to make of the extinction meter and exposure calculator on the top deck; it seems to me to offer little over just making a best guess about proper exposure. I wonder if the extinction meter wasn't conceived of more as a marketing ploy rather than as a practical picture making aid as was the case with the much-touted Autographic feature on the early Kodaks.

I'm sure the amateur photographers of the '30s, '40s and '50s argued at length over the merits of the Argus A and its descendants; and those who get around to trying the camera now probably can find some things to disagree about too. What seems inarguable, however, is the role played by the modest Argus A line in revolutionizing the way that Americans pictured life. Picking up an early Argus camera is a way of taking history into your hands, and making pictures with one provides a tangible link to a past that is otherwise largely beyond reach.

I put quite a few rolls of film through the Argus A2F and posted many of them on the blog.

The pictures from the camera show good resolution; they are notable for a unique tonal character, due in part to the low-contrast optics. The capability to shoot very close to the subject in a simple, early 35mm camera makes shooting the Argus A2F an interesting experience.